Auto logout in seconds.

Continue LogoutIn the age of Fitbits and other wearables, consumers interested in living a healthy lifestyle have been trained to strive for 10,000 steps per day. But experts say that goal is arbitrary and isn't backed by evidence, David Cox reports for The Guardian.

The 10,000 steps goal's origin

According to Cox, the 10,000 steps goal is the result of a "successful Japanese marketing campaign" launched in the mid-1960s by sports health company Yamasa Tokei Keiki for what is believed to be the first wearable step counter. The device's name, manpo-kei, translates to "10,000-step meter."

But that number was not grounded in science, according David Bassett, head of kinesiology, recreation, and sports studies at the University of Tennessee. "They just felt that was a number that was indicative of an active lifestyle," Bassett said.

The flimsy science behind the 10,000-step goal

A research team in Japan eventually explored the number and determined that, for the average Japanese resident—who they estimated took between 3,500 and 5,000 steps a day—increasing their daily step count to 10,000 was indeed associated with a reduced risk of coronary artery disease. Since then, several studies have been conducted that seemingly reinforce the 10,000 steps per day goal, which has now been adopted by the World Health Organization, the American Heart Foundation, and HHS.

But Catrine Tudor-Locke of the University of Massachusetts Amherst's center for personalized health monitoring said these studies' findings are flimsier than they appear. The studies generally compared the blood pressure and glucose levels of subjects who are doing 10,000 steps per day with subjects that are doing significantly less—such as 5,000 or 6,000 steps.

The result, Tudor-Locke explained is "the study might find that 10,000 helps you lose more weight than 5,000 and then the media see it and report: 'Yes, you should go with 10,000 steps,' but that could be because the study has only tested two numbers. It didn't test 8,000, for example, and it didn't test 12,000."

In fact, Cox reports scientists have yet to confirm an "upper ceiling" for the number of steps people should take to achieve long-term health benefits. Research is currently underway to test whether 15,000 or 18,000 steps are more beneficial than the traditional 10,000-step benchmark.

But some experts warn that such an audacious goal won't be achievable for everyone, such as those who are older or have a chronic illness. Further, according to Cox, a sudden significant increase in daily activity could have "adverse consequences" for some, while others might be "intimidat[ed]" by the amount of exercise and avoid increasing their physical activity all together.

Is a 6,000-step goal more realistic?

This has prompted some researchers to ask, what is the lowest step goal that would still produce benefits?

Bassett said some research has shown 6,000 steps or more per day is "protective against cardiovascular disease." Other studies have sought to identify a step goal equivalent to the much-recommended benchmark of 30 minutes per day of moderate exercise, finding that 7,500 steps would be an appropriate aim.

Another underexplored question is the intensity at which daily steps should be taken. "More recently, scientists have started looking at cadence, which is the idea of step rate or frequency of stepping," Tudor-Locke said. "When intensity's better, your heart is pounding a little faster, more blood goes through your body, things are crossing the cell wall that need to; all these things are happening quicker."

Regardless, experts say that any amount of physical exercise is better than none.

"We know that sedentary lifestyles are bad, and ... can lead to weight gain, increase your risk of bone loss, muscle atrophy, becoming diabetic and this litany of issues," Tudor-Locke said. With that reality in mind, according to Tudor-Locke, the obsession with 10,000 steps could be counterproductive if it stands in the way of "get[ting] people off their couches" (Cox, The Guardian, 9/3).

Advisory Board's take

Peter Kilbridge, Senior Research Director and Sophie Ranen, Analyst, Health Care IT Advisor

While several aspects of wearable technology—like the myth of 10,000 steps—might be more marketing hype than carefully researched practice, that doesn't mean that providers should overlook the enormous potential of wearables.

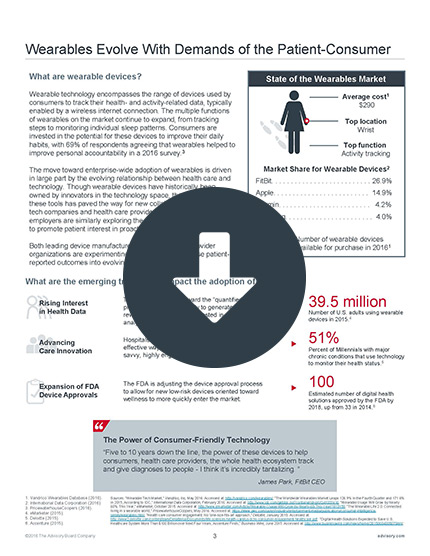

According to a 2018 survey by Accenture, consumer use of wearables has more than tripled since 2014. And the number of companies offering wearable products has also shot up—increasing the data captured from simple metrics like steps, sleep and heart rate, to more complex measures like acceleration, altitude, glucose levels, respiration rate, temperature, and hydration.

So how can your organization benefit from the rise of wearables? Here are two initial ways:

“These patients want a provider who will track this data”

- Boost patient engagement and connect to new patients. Wearables offer a new avenue for providers to connect with patients and increase the number of touchpoints between them (often building greater patient loyalty). Because the type of patients who most often use wearables, "quantified selfers," are typically healthy and active, they are often not as engaged with the health care system. But many recent studies show that these patients are both willing to share their health data with their physician and want a provider who will track this data—offering a new way to engage them.

- Avoid costly chronic care episodes. Many organizations have begun incorporating wearables into care management programs for high-risk or chronic care patients. Integrating wearables not only helps patients track their own health, but also allows them to share this data—giving providers a more comprehensive view of patients than traditionally possible. This is particularly valuable in-between visits, where the data tracked can help to customize care plans and allow providers to potentially intervene if the patient goes off-track.

If your organization is interested in wearables, our research has found that there are three top questions you should consider first:

- Do you have a data management system to turn the large amount of wearable-generated data into actionable information?

- Do you know the HIPAA security obligations that accompany the devices your patients are using?

- How will your wearable strategy compliment your existing clinical programs and tap into the same incentives that you already use to keep patients healthy?

For our insights into how you may want to answer these questions, as well as a deep dive into the main opportunities and challenges that wearables programs face, download our new research report on Incorporating Wearables Data into Clinical Practice.

Your telehealth cheat sheet on wearables

Wearable technology encompasses the range of devices used by consumers to track their health- and activity-related data. As the multiple functions of wearables on the market continue to expand, consumers are becoming more invested in the potential for these devices to improve their daily habits. Wearable technology can help to facilitate patient activation and improve clinical outcomes.

The cheat sheet details how rising interest in health data, advancing care innovation, and expansion of FDA device approvals has impacted the adoption of wearables.

Don't miss out on the latest Advisory Board insights

Create your free account to access 1 resource, including the latest research and webinars.

Want access without creating an account?

You have 1 free members-only resource remaining this month.

1 free members-only resources remaining

1 free members-only resources remaining

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

This content is available through your Curated Research partnership with Advisory Board. Click on ‘view this resource’ to read the full piece

Email ask@advisory.com to learn more

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits Include:

This is for members only. Learn more.

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.