Auto logout in seconds.

Continue LogoutAn increasing number of employers are offering wearables like Fitbits or Apple Watches to their employees in an effort to help their workers lead healthier lives, but some experts are raising concerns about how employees' health data could be used, Christopher Rowland reports for the Washington Post.

Your telehealth cheat sheet on wearables

A growing trend

Employers increasingly are offering employees no-cost or discounted wearables that track workers' step counts, heart rates, sleep durations, and more. According to Rowland, employees typically voluntarily opt in to programs that allow the wearables to share collected data with their employers or the health insurers administering their employer-sponsored health plans. In exchange, employees can be eligible for discounted insurance premiums or reimbursements for other health care costs in return.

For example, UnitedHealthcare has a program called UnitedHealthcare Motion, in which the insurer gives participating workers up to $1,000 a year if they hit certain goals, like 10,000 steps a day with 3,000 of those steps within 30 minutes, and 500 step intervals throughout the day, Rowland writes. Daily Briefing is published by Advisory Board, a division of Optum, which is a wholly owned subsidiary of UnitedHealth Group. UnitedHealth Group separately owns UnitedHealthcare.

The goal of these programs is to help employees get and stay fit, though evidence on whether the programs work is mixed, Rowland writes.

Still, the programs are becoming more common. According to an annual survey from the Kaiser Family Foundation, 14% of employers who offered health insurance in 2017 collected data from their employees' wearable devices, and that number jumped up to around 20% in 2018. In addition, according to ABI Research, annual sales of wearable devices for company wellness programs is expected to hit 18 million in 2023.

The popularity had prompted some wearables to launch new features. For example, Fitbit adding a call service to reach out to employees whose data show they're not hitting their fitness goals, Rowland writes. Adam Pellegrini, SVP of Fitbit Health Solutions, said the goal is to improve the health of a company's entire workforce. "Sustained behavior change is really the focus," he said, explaining, "Through the system, we can actually see who is not hitting their goals, who is not adhering to that action plan."

Privacy concerns

However, some experts are raising privacy concerns about employees' health data, Rowland writes.

According to Rowland, the data collected by the wearables usually is sent to an app on the user's phone, and from there the data could be transferred to a number of different places, including the manufacturer of the wearable and an employee's health insurer, employer, and wellness-plan administrator, Rowland writes.

Joe Jerome, a policy lawyer at the Center for Democracy & Technology, said federal health data protections under HIPAA typically do not apply, since many of the entities receiving the data are not covered under HIPAA and employees are submitting their data voluntarily. "There's gaps everywhere," he said.

UnitedHealthcare said employers often will have access to "de-identified" data from their employees, though they "may receive certain additional information for plan administrative purposes" in some cases.

Further, some experts have raised concerns that companies could use employees' health data to favor the healthiest employees and punish those who are less healthy or who engage in unhealthy behaviors, Rowland writes.

Lee Tien, a senior staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said, "The more that employers know about their employees' lives, especially outside the workplace, off-duty hours, the more potential control or effects they have on their lives in the first place." For instance, Lee said it's possible that, based on a worker's health data, there could "be effects on whether [the worker is] retained, promoted, demoted," or "laid off."

In addition, Rowland writes that employees' health data could be paired with information from outside the health system, such as workers' credit scores, allowing companies to create "individual risk forecasts" for each person.

"The Fitbit or Apple Watch applications … may yield clues to things about you that you are not even aware of, or not ready for other people to know," Tien explained, adding, "Individuals and consumers who are buying these devices don't understand that is a potential consequence" (Rowland, Washington Post, 2/16).

Your telehealth cheat sheet on wearables

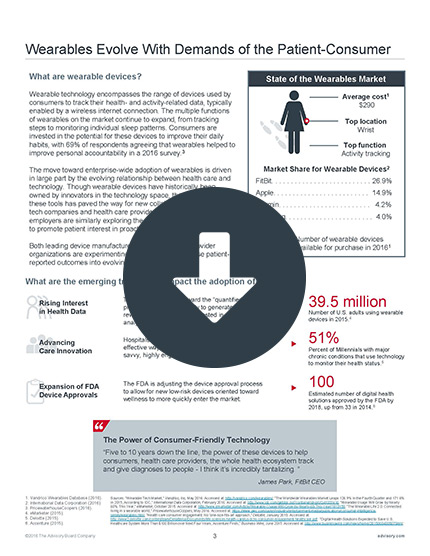

Wearable technology encompasses the range of devices used by consumers to track their health- and activity-related data. As the multiple functions of wearables on the market continue to expand, consumers are becoming more invested in the potential for these devices to improve their daily habits. Wearable technology can help to facilitate patient activation and improve clinical outcomes.

The primer details how rising interest in health data, advancing care innovation, and expansion of FDA device approvals has impacted the adoption of wearables.

Don't miss out on the latest Advisory Board insights

Create your free account to access 1 resource, including the latest research and webinars.

Want access without creating an account?

You have 1 free members-only resource remaining this month.

1 free members-only resources remaining

1 free members-only resources remaining

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

This content is available through your Curated Research partnership with Advisory Board. Click on ‘view this resource’ to read the full piece

Email ask@advisory.com to learn more

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits Include:

This is for members only. Learn more.

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.