Auto logout in seconds.

Continue LogoutEvery clinician strives to comprehensively address patient’s individual biopsychosocial needs. In a perfect world, delivering on this commitment would result in equitable care that meets all patients’ needs. And yet, ample evidence indicates that disparities in care delivery and outcomes persist at the point of care.

- 22% less likely that Black patients report receiving pain medication than white patients

- 70% of transgender or non-binary patients report experiencing discrimination in health care

- 3x more likely that a Black newborn dies in the hospital, compared to a white newborn, when cared for by a white physician

- 0.75-1.47 days longer LOS for patients who do not receive professional interpretation services

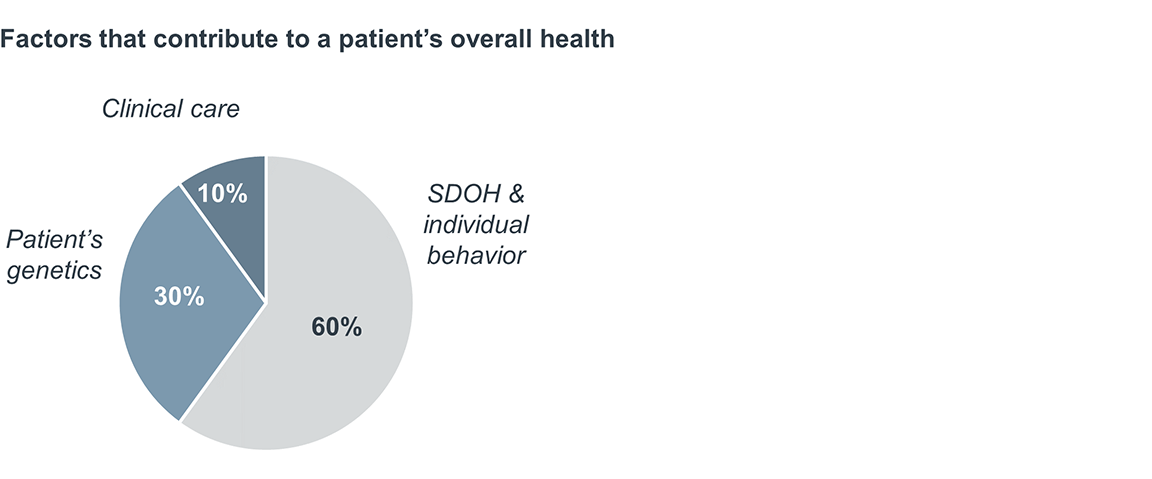

- 50% of readmissions are caused by social determinants of health

This unwarranted variation in care is often the result of pervasive systemic and societal challenges that go far beyond any particular caregiver, setting, or health system. In light of the stark patient population disparities revealed by Covid-19 and the national dialogue around historical and modern-day inequities, every health care organization has a renewed mandate to address disparities.

Many organizations are invested in advancing health equity, diversity, and inclusion within their organizations and communities. Their efforts to date have typically focused on increasing workforce diversity and staff training.

The theory behind increasing workforce diversity is: a workforce that more closely matches the demographics of a local population may be able to provide more culturally sensitive care. Staff with more diverse backgrounds may better understand patients’ realities and identify organizational blind spots.

The goal of training is to help staff recognize their own innate biases, thus enabling them to provide culturally sensitive care to all patients, especially those whose background and culture are different. Typical training topics include diversity and inclusion, implicit bias, and patient care guidance for specific non-dominant populations.

The clinical executive’s role in reducing disparities at the point of care must go beyond increasing workforce diversity and staff training. These initiatives are important but not sufficient to close the massive disparities that persist in our industry.

Increasing workforce diversity to match local community demographics will take years, if not decades. It is a worthy ambition that will yield dividends: more diverse and inclusive teams have a 17% increase in team performance, 20% increase in decision-making quality, and a 29% increase in team collaboration. But organizations can’t afford to wait to achieve “ideal” workforce demographics before turning to additional strategies to reduce disparities at the point of care. And even if an organization achieves a diverse workforce that perfectly mirrors the local patient population, this diversity alone won’t solve health disparities. Systemic issues within organizations and pervasive inequities beyond the point of care will persist.

Thoughtful training can help staff become more aware of disparities and their own innate biases. But even the most rigorous, widespread training will not eradicate systemic issues contributing to disparities. Organizations must go beyond workforce initiatives to make progress in reducing disparities.

Since this work will require additional investment, all clinical executives must be able to make a strong business case for reducing disparities, in addition to the moral and mission-based arguments for equitable care.

Consider one example of a disparity at the point of care: inconsistent and inadequate language services (such as interpretation and translation) for limited English proficiency (LEP) patients. Language barriers often prevent meaningful communication between clinicians and patients, which compromises care quality. When compared to English-speaking patients, LEP patients have a higher risk of adverse medical events, longer hospital stays, and higher readmission rates.

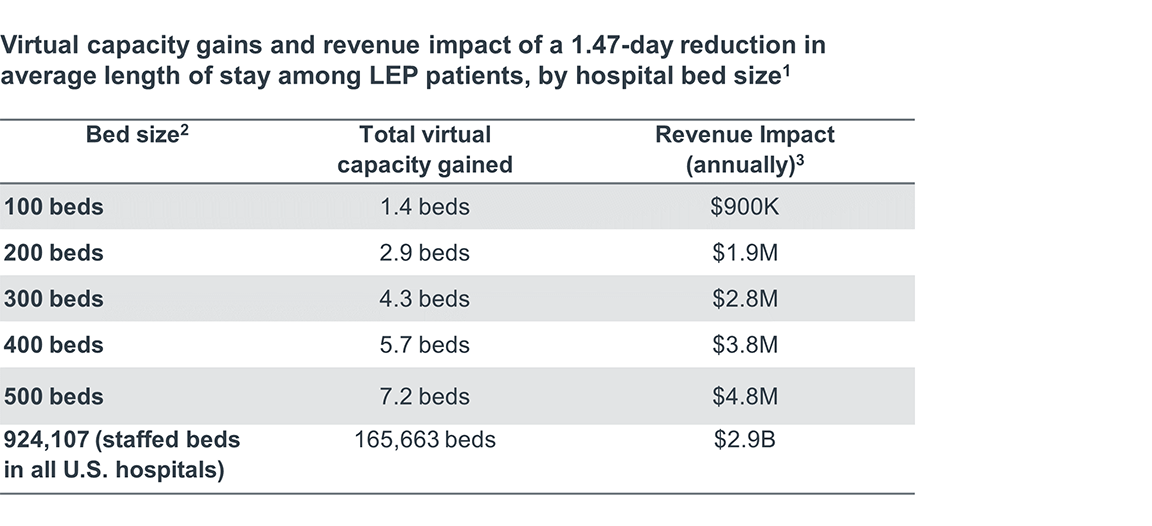

One study found that LEP patients who did not receive professional interpretation services at admission or discharge had an increase in their length of stay of up to 1.47 days. By providing comprehensive interpretation and translation services to LEP patients, organizations can begin to reduce the disparity and provide a more equitable experience.

There are additional financial benefits for the organization. To demonstrate the effect of reducing this particular disparity, the table below shows the number of “new” beds in virtual capacity that can be added by eliminating the excess length of stay for LEP patients.

Based on the model, reducing the average length of stay for LEP patients by 1.47 days generates over $923,000 annually for a 100-bed hospital. And that number grows with bed size: $4.8 million for a 500-bed hospital, and almost $2 billion across the country.

This analysis is one of many examples of how eliminating disparities can simultaneously improve both care quality and efficiency.

Data-driven examples such as the analysis shared above can rally stakeholders around the need to address health disparities. We recommend that all organizations looking to reduce disparities build their strategy around the following dimensions.

- Governance: Do we have a leadership structure that can develop an organizational strategy to address health equity?

- Social needs and community outreach: Are we addressing community-wide social determinants of health and their root causes?

- Data collection: Do we collect quantitative and qualitative patient data to improve care and support identification of disparities at the population level?

- Data analysis: Do we analyze our data to identify health disparities in our patient population?

- Goals: Do we set measurable goals for reducing disparities?

- Staff knowledge, skills, and attitude: Do we provide comprehensive skill-building training for our staff?

- Culturally sensitive care delivery: Do we provide culturally sensitive care to every patient who enters our system?

- Workforce diversity, equity and inclusion: Do we employ people from our community and build a workforce and organizational culture that reflects our patient population?

We recommend executive teams use our maturity model for reducing health disparities to assess their current level of maturity for each of these dimensions.

Clinical executives should take an active role in helping to set strategy and drive implementation across several, if not all, of these dimensions. However, reducing health disparities is a massive, long-term, multidisciplinary challenge, so it’s important to identify exactly where clinical executives should prioritize their personal efforts. This publication details where clinical executives should focus.

Clinical executives must focus disproportionally on four strategies. These are areas where they can have an outsized impact on organizational strategy, either through direct leadership or advocacy.

Reducing disparities at the point of care is a critical first step toward providing better care for everyone. But an organization won’t make real change in the community unless its leaders commit to addressing the structural root causes of SDOH: poverty and inequity. Addressing these root causes is an essential commitment for any organization that embraces its role as an anchor organization in their community. Anchor organizations invest in long-term health equity by considering what business, workforce, and culture changes they must make to address the root causes of SDOH. These organizations actively reinvest in their communities to improve their socioeconomic status. This involves advocating at the local, state, and federal level for policies that address structural barriers to health care access, socioeconomic advancement, and equity, as well as investing in local economies to build sustainable and equitable wealth.

Don't miss out on the latest Advisory Board insights

Create your free account to access 1 resource, including the latest research and webinars.

Want access without creating an account?

You have 1 free members-only resource remaining this month.

1 free members-only resources remaining

1 free members-only resources remaining

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

This content is available through your Curated Research partnership with Advisory Board. Click on ‘view this resource’ to read the full piece

Email ask@advisory.com to learn more

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits Include:

This is for members only. Learn more.

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.