Auto logout in seconds.

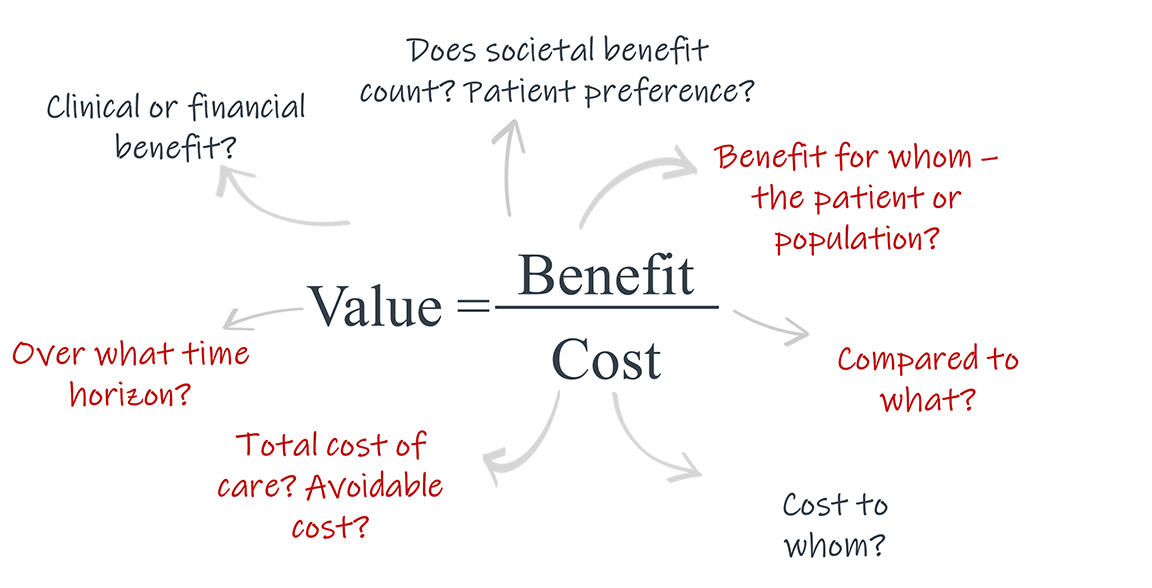

Continue LogoutDefining health care value is tricky, especially when there is no shared consensus of benefits and costs and the lack of a single 'decider' to arbitrate the often-conflicting interests of stakeholders. One that that is clear is that today's approaches to value must evolve as new and impending products challenge the existing paradigm.. Historically, health plans and prescribers relied on the limited set of randomized control trials(RCTs) used for FDA approval, along with a short-term cost over benefit calculation to determine whether a drug would provide value to a patient. Given the rising costs and substantial patient care implications of emerging, disruptive clinical products, relying on these metrics alone is no longer sufficient.

Moving forward, this will require life science organizations to forge a deeper understanding of how other stakeholders define benefits and costs and how that's evolving with new products.

Exacerbating this need for a different approach to value is the pipeline of innovative products coming to market. For example, million-dollar drugs are gaining market approval without the decades of data necessary to definitively prove the durability of their positive impact.

A few examples of the common points of contention in defining value as an outcome of treatment are:

The tradeoff between value for the patient and population – Given concerns over total cost of care, decisions that may be optimal for individual patients would not be optimal when taking a population level approach and weighing the relative costs and benefits of treatment.

Exemplar products: deep brain stimulation, ultra high-cost drugs.

Determining time horizons – The price tags and reimbursement approaches for newer therapies create additional hurdles around the time horizon in which value is delivered. Many novel products require longitudinal and other data that goes beyond what is required by regulators and/or have benefits that accrue over a timeframe beyond the typical commercial health plan focus.

Exemplar products: ultra high-cost drugs, digital therapeutics (DTx).

Increased lack of direct comparators – The rise of non-pharmaceutical interventions is making it harder for life science organizations, manufacturers, payers, and regulators to compare across potential treatments.

Exemplar products: digital therapeutics (DTx).

Identifying and quantifying avoided costs – As diagnostics become more precise, this creates challenges to demonstrate return on investment (ROI).

Exemplar products: pharmacogenomics and biomarker testing.

Because traditional treatment paradigms are being disrupted, life science stakeholders must take a more coordinated, expansive approach to data collection, evidence-generation, outcomes monitoring, and value assessment. Challenges such as high upfront costs of treatments, lack of comparators for first-in class and orphan drugs, reduced decision-making time due to FDA fast-tracking, and increased complexity of technologies and therapies signal that stakeholders need to take action.

To do so, they will need to ask new and different kinds of questions about data availability and integration. Additionally, they will need to think differently about study protocol designs to ensure recruitment of representative samples due to a potentially limited subject pool because of the nature of treatment .This will also require life science companies to consider how to collect real-world data, and find opportunities for support and profitability.

The role of life science organizations should be to find ways to partner with payers and HTAs in assessing value and finding common ground. Life science organizations should grapple with the following questions to start to establish a new paradigm and demonstrate value despite these challenges:

- How are we going to define value for our products, and how can we structure our value assessment framework to address unmet needs of patients?

- Which time horizons and endpoints best demonstrate value and impact? How does that vary by stakeholder?

- How do we align internal incentives to maximize the impact of our collective efforts?

- How can we take an ecosystem approach to thinking about evidence circulation and influence?

Life science organizations are uniquely situated within the healthcare ecosystem due to their knowledge sharing and exchange of clinical insights across stakeholder groups and have an opportunity to improve processes across sectors to achieve medical value.

After speaking with leaders in this space, we’ve identified three imperatives for life science organizations to tailor and target their value assessment framework to account for disruptive clinical products:

It is imperative to expand value frameworks to catalyze more impactful evidence generation strategies, craft value narratives, and ultimately optimize patient outcomes. Life science organizations must shift from looking at one-time costs and immediate clinical outcomes to a broader set of value drivers to help payers approve products and create the optimal case for market adoption by appealing to endpoints that create value for both patients and providers. A broader set of value drivers includes the opportunity cost of not treating a patient, the overall impact on total cost of care, and patient preferences or quality of life. As critical as it is to get patients to the care they need, it’s even more important to ensure that the entire care pathway is accounted for in a holistic manner to determine the true benefit of a new clinical product.

Life science leaders should be aiming to ensure data is transformed into evidence that meet both patient and population needs.

Questions for life sciences leaders to consider:

- What kinds of real-world evidence meaningfully inflect choices about product access and use?

- How do different “types” of payers weigh health economic data? What metrics beyond safety and efficacy have the greatest salience with different kinds of payers?

- What partnership models are payers willing to engage in to expand the time horizons they consider for value?

- When in the product lifecycle can changes in data collection and evidence generation create meaningful impacts on payer and provider perception of value?

Expanding the definition of an influencer

Because value means something different to each stakeholder, it is critical for life science organizations to understand a multitude of viewpoints so that they in turn can support the rest of the healthcare ecosystem in achieving medical value.

Life science leaders need to think beyond one source or channel of evidence dissemination and understand how different sources of information and influence interact. In the past, most targets of medical strategy have focused on key opinion leaders(KOLs) as “key influencers.” While KOLs remain an important part of information dissemination and clinical consensus, other influencers such as DOLs are increasingly able to change perceptions of products and companies. Some examples include:

Because of this, non-traditional perspectives should be leveraged as these groups can be beneficial partners to life sciences organizations in the education and marketing for newer products, as well as data tracking.

Additionally, consulting a broader range of external stakeholders creates diverse insight generation. A parallel shift that is occurring is the shift from a model of evidence dissemination to one where it is vital to understand how evidence circulates to create medical consensus. Life science leaders generally should be taking an “ecosystem approach” to thinking about evidence circulation and influence by looking at social data, journals, blogs, conferences, etc. and mapping out the interplay of patients, physicians, and other influencers.

Questions for life sciences leaders to consider:

- How can life science leaders overcome the internal siloes with HEOR, regulatory and market access that limit the effectiveness of evidence generation to meet all customers’ demands?

- What communication tactics are most effective to translate insights from the field into product/TA strategy?

- What is the most effective way to disseminate field-based value stories throughout the entire organization?

- Which strategies for evidence dissemination (e.g. publications, conferences, office visits) are most effective to reach different providers archetypes (e.g., physicians, KOLs, risk-bearing providers?)

- How can you use conversations from online clinician communities to better understand HCPs’ uses and perceptions of your products as well as current evidence needs?

Designate teams to alleviate administrative burdens

Many stakeholder groups struggle to identify who is (or should be) responsible for capturing and tracking outcomes data. This challenge is made more complex as physicians are already burnt out and not reimbursed for the additional tasks of data collection, tracking patients, and providing back data. As health care leaders struggle with these challenges, they are increasingly looking to adopt risk-sharing finance models to create accountability for cohesive, patient-centered care delivery through value-based care.

Life science organizations must identify practical ways to partner externally, aggregate data, and incentivize its collection through designated teams. An example of this is Optum’s approach to alleviate payers’ data adjudication burden by outcomes-based programs. Third parties are responsible for verifying payers and providers, assessing patient health status across the care continuum, and identifying outcome events. Most notably, this program leverages claims and other clinical data to ensure understanding of outcomes and patient segments to create value for all stakeholders.

Questions for life sciences leaders to consider:

- How can we streamline data management, analysis and use?

- How do we coordinate data requests and uses between internal organizations?

- How will we determine what the source of outcome data is, and in turn, which metrics to choose?

- How do we get stakeholders to not only accept outcomes-based contracting, but to accept the viability that comes with it?

- How should our data collection strategy adapt for market dynamics like site-of care shifts to gather the data necessary to provide localized insights?

Payers, regulators, patients, and providers have different incentives and perspectives when it comes to measuring meaningful impact. For example, payers may argue that if a drug or therapeutic does not provide meaningful clinical improvement and reduction in health costs, that treatment is not beneficial while providers may feel that any change in a patient’s clinical pathway may be sufficient and justified, regardless of reduction in cost.

Life science leaders have a responsibility- and opportunity- to step in and incorporate alternative perspectives and directly have an impact on the availability and use of new medications by other stakeholders in the ecosystem.

Real world evidence (RWE), any evidence about a medical product or intervention that comes from outside of a clinical trial, provides insight into real-life treatment outcomes and can offer a more accurate representation about how medical products and interventions work for different patient populations. RWE will be vital to life science leaders' success in demonstrating product value and aligning on time horizons. Because many new products pose a challenge to randomized controlled trials (often due to niche populations, small trial pools/limited trial participants, and ethical concerns over the use of placebos), life science organizations should continuously evaluate clinical products post-trial, and use RWE to fill in evidential gaps to make the case for value.

Additionally, an alternative approach to appeal to payers and gain buy-in is to determine impact and have stakeholders align value end points to a meaningful time-to-impact horizon in order to determine true value.

Because some disruptive therapeutics and diagnostics are durable and/or curative in nature, it is critical that longer periods of monitoring in clinical settings beyond the typical health plan focus are incorporated to prove value for each patient. 12-18 months does not have to be the default for medical value, and increasingly, has proven to fall short of the time it takes to see impactful clinical measures for patients with more complex and severe disease states.

Life science organizations partnering with payer groups should increasingly differentiate financial and clinical endpoints, and determine which endpoints are most beneficial to the individual and population-level total cost of care, compared to endpoints that only align with annual budgets and contracts.

Questions for life sciences leaders to consider:

- How do payers evaluate a treatments’ long-term value when most of their covered patients only remain in-network for a limited time horizon?

- What metrics do payers use to evaluate whether a treatment will impact the downstream utilization of medical services?

- How does the integration of pharmaceutical and medical treatments (e.g., CarT therapy) impact how payers make coverage choices?

- How do leaders leverage real-world data and convince regulators to be more comfortable with less-traditional sources of data?

- How can RWE help us overcome the mismatched time horizons of interest for us and other stakeholders?

- What new metrics do payer and provider stakeholders value for which evidence is scarce?

- What organizational model allows us to get the most value from our RWD assets?

Moving forward, life science organizations must continue to push the ecosystem to iterate and evolve on approaches to defining and paying for value. This change will require persistence and acknowledgement that:

- Many organizations have not shifted their mindset about what constitutes as value, and novel therapies only further exacerbate this issue. Life science leaders will have to consider how new innovations fit within the broader context of care delivery, and how multiple stakeholders working together can ensure that each patient has a holistic care journey. Life science organizations, payers and providers will need to work together to address tensions between population health needs and patient centricity, especially as more therapeutics and diagnostics become more personalized and precise.

- Achieving medical value is hard, and multiple stakeholder incentives make accounting for it harder. Multiple stakeholder incentives make defining time to impact difficult, however, life science organizations should be aligning time horizons to endpoints that best demonstrate value when working with multiple payer groups. Life science organizations will need to re-define the scope of assessment in order to avoid value misalignment and suboptimal metrics and data measurement.

- Lastly, meaningful progress will require candid dialogue between leaders in industry, health care delivery, academic medicine, and patient advocacy groups. The idea of a KOL is changing, and life science organizations should be taking a “ecosystem approach” to thinking about evidence circulation and influence. Abandoning the idea of identifying value in silos and working towards a shared understanding is the path forward.

Don't miss out on the latest Advisory Board insights

Create your free account to access 1 resource, including the latest research and webinars.

Want access without creating an account?

You have 1 free members-only resource remaining this month.

1 free members-only resources remaining

1 free members-only resources remaining

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

This content is available through your Curated Research partnership with Advisory Board. Click on ‘view this resource’ to read the full piece

Email ask@advisory.com to learn more

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits Include:

This is for members only. Learn more.

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.