Auto logout in seconds.

Continue LogoutOverview

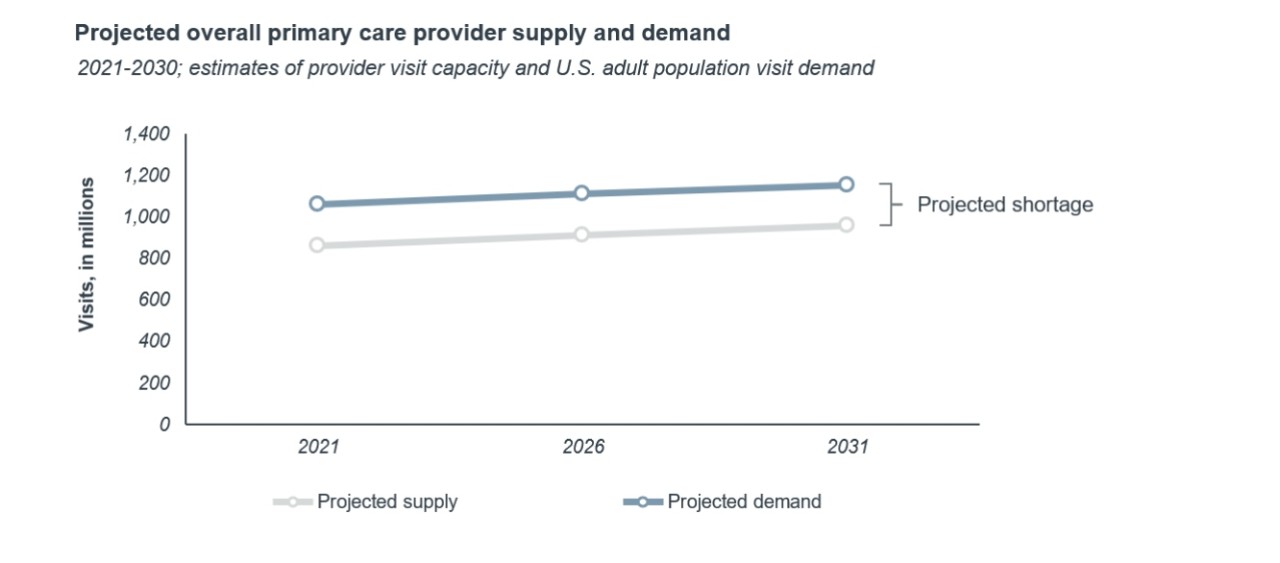

The United States seems to be on the brink of a severe physician shortage. Demand for primary care will far outpace physician supply as the population continues to grow and age, but the rate of physicians entering the workforce stays roughly the same. It seems inevitable that physician shortages will worsen access to care and burden practicing physicians for years to come.

But a true shortage is not inevitable. Our analysis shows that primary care leaders can avoid a shortage in care supply by adopting proven productivity improvement strategies.

The United States faces an inevitable primary care physician (PCP) shortage. Patient volumes, administrative burdens, and limited workforce growth have led to a shortage in PCPs. Furthermore, new demand from a growing, aging, and increasingly complex population will far outpace new workforce entries from physicians and advanced practice providers (APPs).

This shortage will worsen access to care and burden practicing physicians for years to come.

Administrative burdens and operational efficiency keep the current physician workforce from practicing to its full clinical capacity. By addressing those challenges, health care leaders can prevent a physician shortage.

We crunched the numbers and found that there would, in fact, be a small shortage of primary care providers if nothing changes. However, we then evaluated how interventions in four categories would affect primary care visit supply (workflow optimization, care team redesign, telemedicine, and enabling technology). Even in our most conservative estimates, these interventions increase physician capacity to far exceed demand: a physician surplus rather than a shortage. Getting as tactical as possible, we found implementing just one intervention from each of the four categories would yield a 40% increase in PCP capacity and eliminate the shortage.

Shortage models assume static productivity

Physician workforce growth is too slow to prevent a shortage

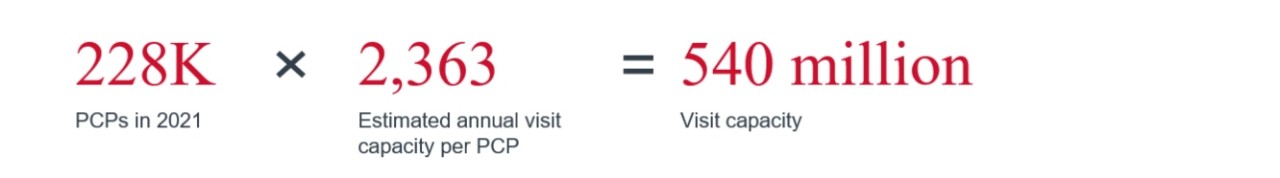

If we assume workforce growth is the only driver for increased capacity, a primary care shortage seems inevitable. The average PCP currently sees an estimated 2,360 visits per year. At that rate, we would need to add tens of thousands of PCPs to meet present demand.

Even fast-growing, fully autonomous APP workforce would not meet demand

APPs are projected to be one of the fastest growing health care roles across the next 10 years. More practices are elevating the role of APPs to manage patients autonomously, and more states are allowing APPs to see their own panels. If we assumed that APPs could see the same number of patients as PCPs without any physician support, we would expect an additional supply of 322 million visits.

Despite that additional capacity, projected demand still far exceeds the number of visits a combined physician and APP workforce could manage.

There is not a primary care shortage

By focusing on workforce growth as the only lever to increase visits, most primary care supply models make a shortage appear inevitable. What these models overlook is the misapplication of physician time and capacity.

Staff and workflow innovations increase clinical capacity

Workflow changes can increase primary care visit capacity by 40%

By focusing on reallocating provider time instead of growing the workforce, physician leaders can prevent a shortage. We analyzed four different types of primary care workflow interventions. In total, we looked at 11 specific tactics that leading organizations have implemented to increase physician capacity and allow them to spend more time on clinical care and less time on administrative work:

Holistic care team redesign

- Increased MA staffing

- Codifying roles across the care team

Workflow optimization

- Efficiency-oriented physical design

- Continuous EMR training

- Pharmacists focused on high-risk patients

- Dedicated staff for referral management

- Medication refill protocols

- Filtering patient communication across the care team

Enabling technologies

- Documentation technology

- Assistive clinical technology

Telemedicine

- Asynchronous virtual visits for basic care

Then we tested what impact those improvements could have on PCP supply.

Even our most conservative estimates for added visit supply completely negated the shortage. Instead, we saw a visit surplus that was three times larger than the shortage. This stark difference reflects just how much time is lost to non-patient-facing tasks in primary care, time that can be given back through implementing already proven workflow changes.

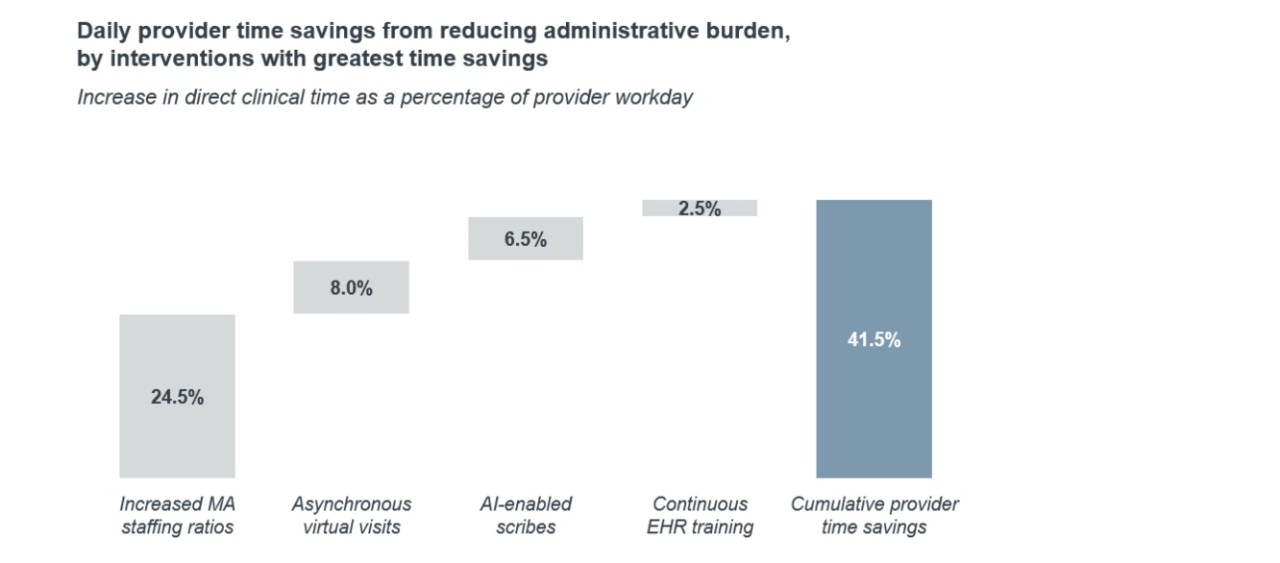

Put in numbers, currently PCPs only spend a third of their time on direct patient care. This means that they’re only able to see about 10 patients per day. We estimate that these interventions increase provider direct clinical time by upwards of 40%, or an additional 10 to 15 visits per day.

A bigger care team has the biggest impact on capacity, but automation may be more feasible

The good news is physician leaders don’t have to implement all 11 strategies to see major improvement.

We analyzed the most impactful intervention in each category and identified them in the chart below. These are the interventions with the biggest bang for their buck and the ones physician practice leaders should prioritize for implementation. Just these four yield less administrative burden, greater physician capacity, and no PCP shortage.

Leaders should weigh their organization’s circumstances when evaluating what interventions are most feasible. But even if an organization can’t do all four of the most impactful tactics, doing one or two still makes a difference—small improvements that can help practices win market share, improve access and patient experience, reduce turnover and recruitment costs, and negate the physician shortage.

Physician leaders have the ability to prevent a physician shortage. But workflow improvement could not only impending access and quality challenges driven by a shortage—they can also improve the working life for physicians.

Take models seriously, but not literally

If the Covid-19 pandemic teaches us anything, it’s how quickly things change in health care. The future supply of physicians is impossible to accurately quantify no matter how perfect the data or calculations.

Be aware of the strain of high provider working hours

On average, PCPs around the nation work more than 50 hours per week. Much of their work happens after clinic hours. More than mitigating a long-term physician shortage, implementing these interventions makes current physician practice more sustainable. For practicing physicians, spending upwards of 75% of their time on patient care instead of desktop medicine will get them back to why most of them wanted to go into medicine in the first place: to care for patients. For physician leaders, a better work-life balance gives an organization an advantage when recruiting new physicians and retaining existing ones.

You have more agency than you might think

Our analysis shows there is a lot within a provider organization’s control to increase their primary care visit supply. Organizations can and should make these care model and technology changes now—not just to offset a future shortage but to ease the burden on their current workforce.

Despite that additional capacity, projected demand still far exceeds the number of visits a combined physician and APP workforce could manage.

Provider supply

We considered both PCPs and advanced practice providers (APPs) in supply, accounting for departures and entrants over the next decade. Then, we converted the number of providers into clinical hours and visits per year to get projected supply of visit capacity.

Provider demand

We estimated current annual demand by applying the average annual visit number per primary care provider from our Integrated Medical Group Benchmark Generator to the entire U.S. adult population. We then applied population growth projection to estimate future demand. Those estimates are in line with external analyses, such as from the AAMC.

Impact of workflow interventions

After segmenting current provider time worked into administrative or clinical, we identified several primary care workflow interventions with vetted data that reduce provider administrative burden or increase their visit capacity. Then, we determined how many visits (or fractions of a visit) each intervention could produce per provider. We calculated how much each intervention could increase visit supply at conservative, moderate, and aggressive levels.

This analysis was based on the principle that physicians can’t work more hours, but their time can be redistributed from administrative tasks to more clinical time. We also projected all three estimates forward to 2030 based on simple assumptions on population growth and estimates of provider supply from external sources. We then compared these measures to capture presence of a shortage.

Don't miss out on the latest Advisory Board insights

Create your free account to access 1 resource, including the latest research and webinars.

Want access without creating an account?

You have 1 free members-only resource remaining this month.

1 free members-only resources remaining

1 free members-only resources remaining

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

This content is available through your Curated Research partnership with Advisory Board. Click on ‘view this resource’ to read the full piece

Email ask@advisory.com to learn more

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits Include:

This is for members only. Learn more.

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.