Auto logout in seconds.

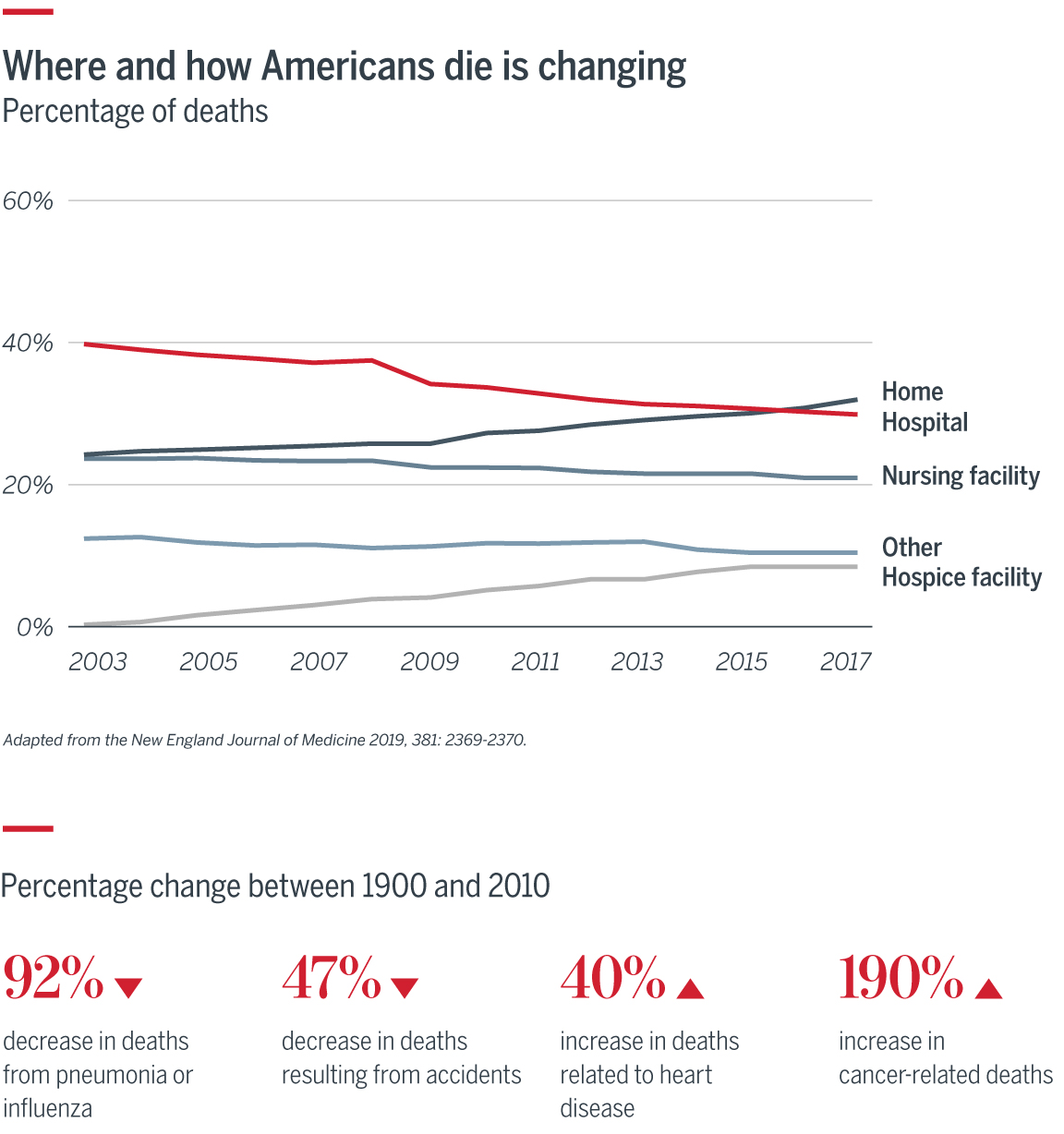

Continue LogoutHow and where Americans die has drastically changed over time. Until the 20th century sudden death was the most common way to die, and home the most common place. After being superseded by hospitals for decades, home has reemerged as the most common place for Americans dying of natural causes.

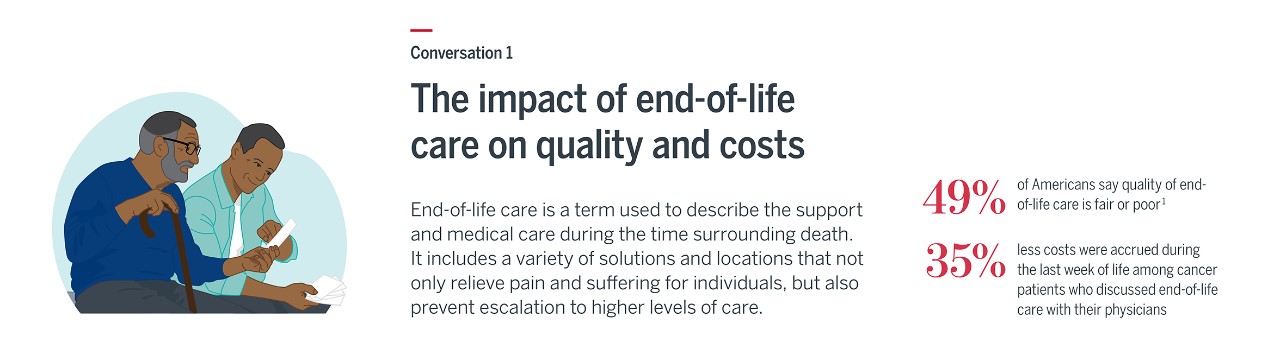

Historically, stakeholders have been hesitant to address death and dying, but we cannot ignore these topics. The changes in means and location of death, along with our rapidly aging population, require better discussions about end-of-life care to reduce confusion around care options and enable the health care industry to meet patients’ needs, reduce costs, and improve quality. Here are three conversations providers, patients, and caregivers should be having about end-of-life care:

Better understanding of options can improve quality of care. When everyone involved understands what is possible, a person approaching death can have better relief of suffering—there is more respect for the individual’s dying wishes. Additionally, understanding the options and having better conversations around end-of-life care can lead to fewer ICU stays, fewer hospitalizations, and reduced utilization of treatments such as chemotherapy. However, societal fears about death and dying have kept stakeholders from realizing the benefits of end-of-life care.

- Common end-of-life solutions: Home care, hospice, palliative

- Common end-of-life locations: Hospital inpatient, long-term care facility, home

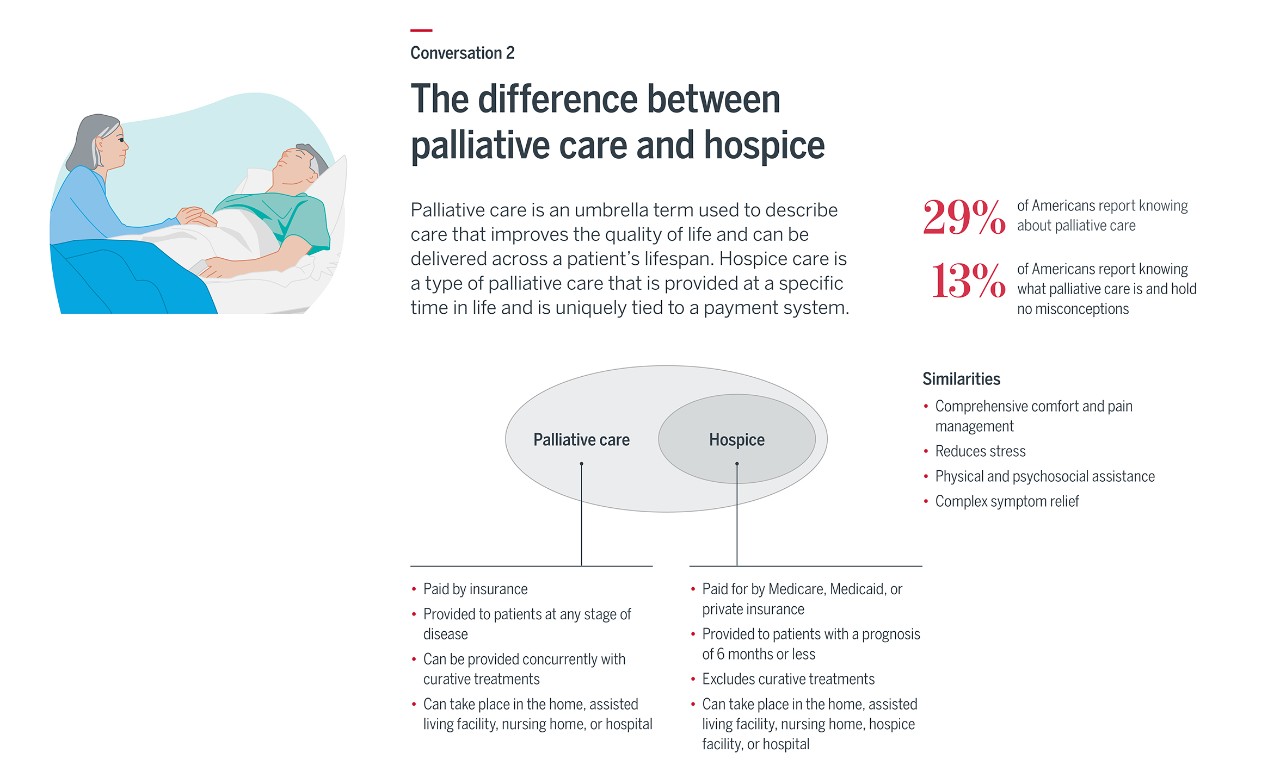

Confusion around hospice and palliative care is a perennial problem—one that has kept many patients from receiving the right care in the right location. Both focus on the care, comfort, and quality of life of a person with a serious illness, but hospice is administered only when a patient has a prognosis of six months or less. Most patients in hospice care must also forgo curative treatments. A doctor or palliative care team will usually manage a patient over the course of treatment, transferring the patient to hospice care when appropriate.

The ability to continue receiving curative treatment during hospice care—known as concurrent hospice—is not a widely accepted. However, unlike the Medicare hospice benefit, the Veterans Administration (VA) does not require patients to end curative treatment in order to enroll in hospice (Sources: VITAS and NIH, Tricare).

Demographic and industry changes have pushed doctors to rethink how they consult with patients about end-of-life preferences. Some experts argue that today’s prevalent approach to advance care planning has fallen short, since patient preference often changes when faced with death. So, there is a push to not only start conversations with patients earlier, but also equip patients with the necessary tools to help make tough decisions in the moment. (Source: NYT)

Although advance care planning isn’t a perfect solution, it is the best current way to understand patient decisions before a health event occurs. Common components to advanced care planning include:

- Health care power of attorney/health care proxy: A legal document that appoints another person to make health care decisions on behalf of the patient if they are incapable of making those decisions on their own.

- Do not resuscitate order (DNR): A physician order, inserted into the patient’s file at the patient’s request, against providing CPR or advanced cardiac life support (ACLS).

- Advance directive/living will/medical directive: A document in which a person decides what treatments they do not want if they are diagnosed with an incurable condition and can no longer make their own medical decisions.

- Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST): A brightly colored, single-page medical order that outlines patient preferences about the types of care they will receive.

For more senior care resources—including our glossary on common terms related to senior care—go to advisory.com/seniors.

1. KFF.org, "Views and Experiences with End-of-Life Medical Care in the U.S."

2. HealthAffairs.org,

Explore the collection of resources that our team has developed to help you understand how the industry is currently caring for older adults (ages 65+), why change is essential, and how industry stakeholders can collaborate to build a better care model for seniors.

Don't miss out on the latest Advisory Board insights

Create your free account to access 1 resource, including the latest research and webinars.

Want access without creating an account?

You have 1 free members-only resource remaining this month.

1 free members-only resources remaining

1 free members-only resources remaining

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

This content is available through your Curated Research partnership with Advisory Board. Click on ‘view this resource’ to read the full piece

Email ask@advisory.com to learn more

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits Include:

This is for members only. Learn more.

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.