Auto logout in seconds.

Continue LogoutAs populations have become more diverse across the last several decades, researchers have increasingly examined the health disparities across specific groups to uncover the root causes of these disparities. One major contributing factor to disparate outcomes is inequity at the point of care—when care teams don’t adequately meet the needs of historically marginalized or vulnerable patient groups. Inequity at the point of care can range from an insufficient understanding of patient needs to bias (implicit or explicit) and discrimination, which can lead to miscommunication, patient distrust, and worse clinical outcomes for at-risk groups.

To address the needs of changing communities and bolster health equity efforts, provider organizations began to strive for cultural competency—also known as cultural congruency, cultural proficiency, or culturally responsive health care. This refers to a clinician’s ability to deliver health care tailored to a patient’s cultural and social context. The concept, which first appeared in the academic literature in 1989, has gained attention and been adopted by health care organizations in the years since then. Traditional models of culturally competent care tend to have two components:

- Language services: In-person, telephonic, and virtual interpretation for patients who are hard of hearing or have limited English proficiency (LEP).

- Cultural competency education: Training and tools (such as checklists or reference guides) about different racial, ethnic, religious, or cultural groups that are prevalent in the health system’s community, with information on how their values or traditions may impact care preferences and behaviors (e.g., religious dietary restrictions).

These models have shown some success. While connecting patients to language services has improved quality outcomes, the evidence is both mixed and incomplete when it comes to cultural education for staff.

Given the mixed evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of cultural competency education on patient outcomes, along with persistent trends in disparate treatment at the point of care, leaders must rethink how, and even if, cultural competency fits within their organization’s broader health equity strategy. Moreover, organizations looking to achieve elusive and illusory “competency” run the risk of causing harm by perpetuating stereotypes about specific identity groups.

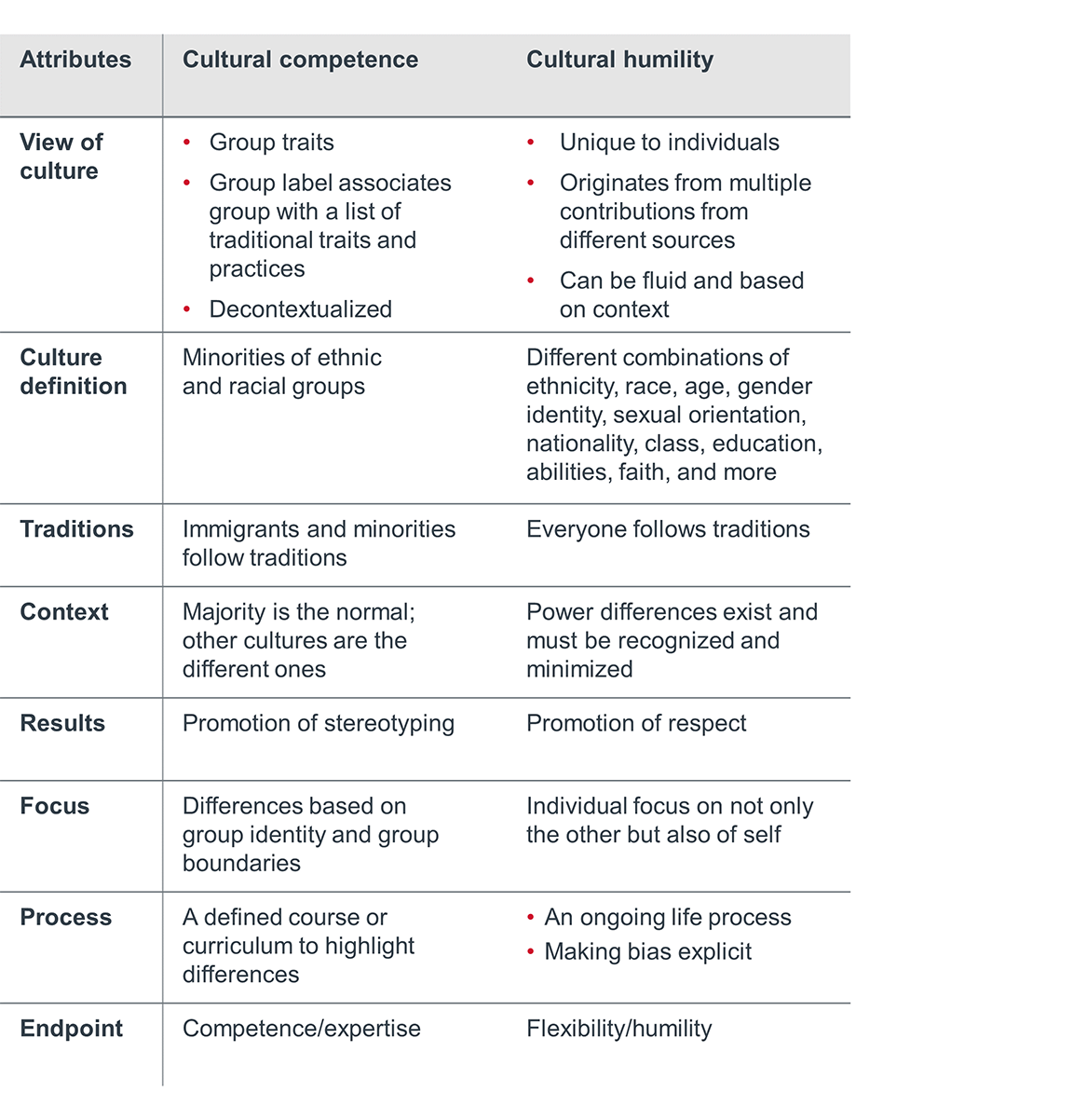

Rather than striving in vain for clinicians to achieve “competency,” provider institutions should aspire to cultural humility at the organizational level. In contrast to traditional competency-based frameworks, cultural humility has no end state. It requires ongoing learning, self-reflection, and skill-building for how to understand a person's cultural context through that person’s own lens. The goal is a true shift in mindset. The focus shifts from interacting with people who are "different" from a perceived norm (reinforcing their “otherness”) to appreciating the inherent value of others’ perspectives and cultures. Cultural humility embraces the notion that it's simply not possible to become truly competent, let alone an expert in a culture or lived experience that is not one’s own. Instead, cultural humility mean that institutions and individuals are humble—that they don’t consider their norms better than any other. They listen to listen to and learn from people's lived experiences. Practitioners of cultural humility routinely interrogate their own identity and lived experiences, and reflect on how they influence their interactions with others.

Cultural humility is a lifelong process of self-reflection and self-critique whereby the individual not only learns about another’s culture, but one starts with an examination of her/his own beliefs and cultural identities.- Katherine A. Yeager and Susan Bauer-Wu, Applied Nursing Research

Yeager and Bauer-Wu’s comparison of cultural competence and cultural humility models

A cultural humility framework can strengthen legacy approaches in two ways:

1. Reinforcing patients’ humanity, rather than “otherness” by practicing true person-centered care

No one’s identity is generalizable, and groups aren’t monolithic. Each person’s identity is uniquely formed at the intersection of one’s gender, sexual orientation, physical and cognitive abilities, age, race, ethnicity, nationality, immigration status, family, community, social needs, passions, and more. It’s not possible to become “competent” in another culture with a brief overview, much less fully understand the nuances of another person’s lived experiences without deeply knowing them.

Cultural humility, therefore, focuses on delivering true person-centered care in a manner that honors a patient’s identities. This includes things like:

- Asking what name and pronouns every patient uses, documenting that information in the EHR, and using it in communications with patients and family members and during key care protocols, like patient identification and handoffs.

- Employing techniques such as motivational interviewing to find out what patients value most—in their care, and in life—to craft an effective care plan that meets each patient’s unique definitions of success.

- Screening all patients for limited English proficiency and offering access to comprehensive language services.

2. Illuminating that we all play a role in delivering equitable care to patients– as individuals and, more importantly, as institutions

Traditional approaches based on cultural competency focus too narrowly on adjusting the interpersonal behaviors of frontline staff. While important, this strategy doesn’t acknowledge that staff operate within the larger organization’s cultural ecosystem. Leaders who don’t address the institutional drivers of biased or inequitable care, or who fail to build an organizational culture committed to advancing equity, will struggle to make long-term change.

This begins with realizing that the health care institution itself—not just individual caregivers—plays a role in providing culturally sensitive care. To begin to understand the communities they serve, provider organizations must study troubling histories of social injustice that impact their patient populations. Education must include the legacies of structural inequities on a macro-level (e.g., national policies, cultural norms) and a local level (e.g., the provider organization’s role in furthering inequities, social determinants of health).

In addition, care teams using a cultural humility framework must understand uncomfortable truths about themselves. This includes acknowledging one’s own biased thoughts and behaviors as well as inequitable power dynamics between the patient and the provider that impact care delivery (e.g., paternalism).

Acknowledging these injustices helps care teams understand the root causes of poor health outcomes, which can occur because of both systemic and individual failings. In turn, provider organizations and care teams are better able to extend empathy to patients during discrete interactions with the health system and more motivated to drive enduring systemic change at the institution or system level.

Cultural humility is chiefly discussed as a requirement for patient-clinician interactions. And this is for good reason—the model can make a significant impact on building trust, supporting patients’ engagement in their care, and improving outcomes. However, provider organizations must pair this interpersonal focus with an infrastructure of institutional support to create an enduring cultural shift. There are four steps to engendering cultural humility.

Grassroots efforts to engender the cultural change necessary for organizational cultural humility can be effective, but they do not ensure an enduring impact. System leaders must build the infrastructure and direct resources to support such a cultural shift, ensure long-term sustainability, and remove the onus from passionate but busy frontline staff. Consider the following three strategies to instill institutional accountability for culturally sensitive, equitable care:

- Assign executive-level accountability to cultural humility improvement metrics

- Assess internal and external opportunities to advance equity

- Acknowledge the health care organization’s role in contributing to structural inequities

Assign executive-level accountability to metrics for improving cultural humility

Organizations need to identify a leader responsible for engendering cultural humility at the institution level. In most cases, this will be the same leader responsible for leading the organization’s broader efforts to advance equity. Progressive organizations are establishing a dedicated Office of Health Equity or Chief Health Equity Officer role which ties funding to initiatives and ensures best practices spread across the system.

A single leader with the seniority to convene their executive counterparts can align the organization’s strategy around addressing specific metrics related to cultural humility and equity. This person can also ensure that each department’s strategic plan supports these goals. If a CXO-level position is not yet feasible, a current leader at the director level or above should be given purview over equity. That person should have sufficient time to dedicate to these responsibilities.

However, it’s important to make sure that every leader is personally accountable for advancing cultural humility at the organization. This work should not be siloed to one team, but rather should permeate every senior leader’s strategic plan and performance metrics. Executives and senior leaders must be able to articulate how their department’s priorities advance the organization’s broader efforts to engender cultural humility to advance equity. This means a close, collaborative partnership is essential between any formally designated health equity leader(s) and other leaders at an organization (e.g., CEO, CFO, clinical executives, heads of departments, directors, and managers).

Common metrics related to cultural humility include:

- Number and impact of equity initiatives implemented by shared governance councils, community board, and/or employee resource groups

- Staff engagement drivers for inclusion stratified by REGAL demographics (Race, Ethnicity, Gender identity & sexual orientation, Age, Language)

- Staff cultural humility scores

- Representation (%) and retention of diverse staff members

- Representation (%) and retention of community members on governing body and advisory committees

- Quantitative and qualitative community feedback (e.g., patient satisfaction scores, complaints, feedback from community and patient advisory councils)

- Participation in equity education sessions, patient engagement training, and cultural celebrations

Assess internal and external opportunities to advance equity

An organizational commitment to cultural humility requires a sustained assessment of how your organization is—or isn’t—actively making progress against reducing health disparities in your patient population. Organizations must understand the makeup of the communities they serve and uncover the strengths and needs of marginalized and vulnerable groups. To accomplish this, most organizations will need to strengthen their data collection and infrastructure to support a truly data-driven approach to both identification of disparities and ongoing assessment of progress made to address them.

First, focus on improving your organization’s understanding of your patients by collecting both granular demographic data and data on social determinants of health contributing to their health status. Most organizations will need to expand their demographic data collection efforts by obtaining REGAL data at minimum. All patient demographic data should be self-reported to ensure the highest possible accuracy. This demographic data serves as the basis for stratifying clinical outcomes and process-of-care metrics across key demographics to identify disparities.

Health disparity metric picklists

Advancing health equity requires a data-driven approach. Use our health disparity metric picklists to uncover focus areas for your organization.

There are two benefits to collecting data on social determinants of health. The data helps providers ensure culturally sensitive care during specific patient interactions. It also helps organizations make the case for increased investment in system-led interventions and community partnerships aimed at addressing the root causes of patients’ social needs.

Organizations must also have a solid understanding of the strengths and needs of their broader community. A community health needs assessment, done in partnership with local municipalities and other community health care providers, is a common start. Identified needs should inform strategic decisions such as prioritization, resource allocation, and community partnerships. In addition, leaders should regularly assess investments and initiatives to determine their impacts on reducing disparities within patient populations. This type of periodic needs assessment can help organizations understand both the social determinants that impact their current patients as well as the needs of people who are not currently connected to the health care system.

Refer to section 4 of this document, Elevate under-represented voices in strategic decision-making, for more guidance on how to leverage staff, community, and patient feedback to advance equity.

Acknowledge the health care organization’s role in contributing to structural inequities

Provider organizations must take responsibility for historical legacies of inequity that still impact the communities they serve. Doing so signals a readiness to collaborate with community leaders to solve the challenges they face. To start, leaders must educate themselves on the history of structural inequities—and their organization’s role in any injustices. Hospital leaders should consider and discuss openly the following questions:

- What is the history of the health care organizations that serve our community?

- How has our organization mistreated or lost the trust of specific patient groups? Have we taken steps to rectify any injustices?

- How is segregation still reflected in our health care system and the broader community, either in our leadership, staff, or the patients we serve?

- How does access to health care differ among groups in our community? How does our system design make it difficult for underserved populations to access care?

One of the major stumbling blocks to offering equitable, patient-centered biopsychosocial care is fitting new techniques into the care team’s workflow. Often, this boils down to staff not feeling confident that they should or can invest the time necessary for true person-centered care. Staff, especially clinicians but also non-clinical staff (e.g., registration, food services), may feel they don’t have the time or resources to address a patient or family member’s social and cultural context during a specific interaction. To help staff adopt truly person-centered care, organizations must overcome three common misunderstandings:

- Limited understanding of the true barriers to care plan adherence

- Perception that workflow changes will take too much time that staff don’t have

- Confusion about what next steps to take to meet complex patient needs

Dispelling the myths surrounding patient-centered care

Myth 1: Patients are noncompliant, and we can’t change that.

Reality: Language around noncompliance can obscure the underlying reasons why patients are unable to adhere to care plans and self-manage their chronic conditions. Most people want to be healthy, but many experience psychosocial barriers including poverty, food insecurity, trauma, and mental health conditions. Many patients may not have adequate health literacy. Providers must design care plans that are feasible for patients, address these needs, and center on the goals and preferences of the patient, rather than the provider’s clinical targets.

Myth 2: Workflow changes will take too much time.

Reality: Care delivery is more efficient overall when staff identify the root causes of patient complexity. In this case, the health care adage applies: prevention is both more efficient and effective than treatment. Although workflow changes take time up front, care teams who have strong, trusting relationships with patients can design effective care plans at the outset, address unmet needs, and avoid unnecessary escalation.

Myth 3: There’s no way to meet complex, non-clinical barriers to care.

Reality: All organizations that aim to engender cultural humility must have a strategy for meeting patients’ non-clinical social needs—and ensure that care teams understand the strategy. Otherwise, staff may avoid the topic of social determinants altogether.

Community health leaders must make sure providers understand that while they may surface these needs, they’re not necessarily responsible for addressing them. Some organizations may have community resource liaisons or social workers who can refer patients to community partners and social service organizations. Community health workers are particularly skilled at building trust, unearthing non-clinical needs, and finding creative solutions to barriers. Care protocol should dictate who is responsible for screening for social needs, how does a trigger occur for a referral when a need is identified, and who is responsible for connecting patients with resources available internally or in the community. No matter the approach, members of the care team across the continuum need to be able to track non-clinical needs in the EHR and connect patients with social support regardless of where the patient presents.

At its core, embracing cultural humility in care delivery is about delivering whole-person, patient-centered care. Beyond basic skill building for frontline staff, this requires the organization as a whole—including frontline staff, and especially leadership—to take on a growth mindset, continuously exploring questions of identity, power, and privilege through ongoing learning and introspection. This is an expectation for staff that the organization can help set by embracing cultural humility at the institution level and by providing routine educational opportunities for staff. These can take the form of training sessions, book and discussion clubs, employee resource groups, and volunteer opportunities in the community. Training for staff should be experiential and ongoing, and it should reinforce that no one can be a true “expert” in any culture or experience that is not their own.

Instead of looking for a formula for treating different types of patients, care teams should use patient-centered communication to lay the foundation for cultural humility in their interactions. When trying to understand a patient’s needs, clinicians must focus on trust-building and active listening to develop an effective care plan. Tactics include:

- health disparity metric picklists: Address underlying trauma and build resilience

- Patient activation measure: Meet patients where they are without judgment

- Motivational interviewing: Unearth the goals that will drive behavior change

- Shared decision-making and patient decision aids: Inform care plan next steps by elevating patient input

- Teach-back: Ensure patients understand their role in self-management

Beyond a solid foundation in patient-centered communication, staff also need to learn more about identity, power, and privilege—and how those impact the patient experience, quality of care, and health outcomes. As part of the educational opportunities, organizations should help staff critically examine how their own identity and lived experience impacts their perception, underlying assumptions, and privilege. Highlight the historical legacies of structural inequities that impact the community today (e.g., redlining, school funding models), with an emphasis on how the health care system has perpetuated structural racism.

Clinicians must understand that there are not clinically significant differences between races. Training should clarify that differences in health status, disease prevalence, and outcomes between races and other identity groups are not inherent to those groups, but rather are often the direct result of forces such as discrimination during care delivery, structural racism, and white supremacy.

Of particular importance, this should include dispelling common and persistent misconceptions in health care related to race that continue to influence care delivery, such as the racist myth that Black people have higher pain tolerance.

Prioritize the following topics (non-exhaustive) during educational opportunities: health disparities, cultural humility, implicit and explicit bias, systemic racism in health care, social determinants of health, and LGBTQ+ health awareness including gender expression and sexual identity. Consult the following resources to inform how you work with staff on developing their knowledge, skills, and attitudes:

- Resource library: Diversity, equity, and inclusion conversation starters

Leverage a curated list of multimedia resources - Podcast: Radio Advisory’s episode on ’Why racism is a health care issue’

Found on Apple, Google, or Spotify - Cheat sheet: Implicit bias

Mitigate the unconscious biases that harm patients in health care - Cheat sheet: Inclusion

Build an inclusive culture to unlock employees’ full potential

To sustain and evolve cultural humility, leaders must center the voices of marginalized and vulnerable groups—across patients, staff, and the community. Clinicians and administrative leaders often do not reflect the communities they serve or even the diversity of their workforce. When those in power do not understand the experience of marginalized communities, they cannot make decisions that advance equity. To elevate these voices:

- Invest in employee resource groups (ERGs). Offer a safe space for staff with shared identities that may be underrepresented in your workplace (e.g., Black employees, LGBTQ+ employees). Solicit ERG input on your organization on your workforce, patient, and community investments.

- Convene patient advisory councils. Patient advisory councils can provide feedback to make care delivery and experience more culturally appropriate and equitable. Organizations can also appoint patient representatives to sit on internal councils and their board.

- Appoint a community board. Some provider organizations dedicate board positions or form entire community boards with budgetary power to hardwire patient and community input into strategic decisions. These positions should be filled with local, diverse leaders who can evaluate health equity investments.

These groups can only be as effective as the power and voice they are given in decision-making for the health system. Ensure that executives sponsor these groups and that they have resources to effect meaningful change. Additionally, audit your existing internal councils that have purview over patient experience, care quality, population health, and care innovation, and ensure there is diverse representation within those groups.

Engendering cultural humility across an organization, the workforce, and within each staff member can be a complex and sometimes overwhelming process. Setbacks and missteps are natural, so champions of equity must regularly evaluate progress, reflect, gather more input, learn from missteps and failures, and make necessary changes over time.

As one progresses on what is a lifelong journey of cultural humility, consider the two next-level approaches detailed below.

- Expand the mandate for cultural humility across the industry.

Hold other stakeholders beyond hospital and health systems (e.g., health plans, life sciences organizations) accountable for adopting the cultural humility framework. As your organization forms partnerships with other organizations, ensure they are an appropriate fit from a cultural and values standpoint, and help them instill similar accountability for equity at their organization. - Advocate for structural change.

Now that you understand the root causes of inequities, determine how you as an individual and how your organization can address them and advocate for your community. Some hospitals and health systems develop a department for policy advocacy to lobby for community health priorities on a local, state, and federal level. Others embrace their role as an anchor institution in the community and take strategic steps to uplift the socioeconomic outcomes of their communities.

Don't miss out on the latest Advisory Board insights

Create your free account to access 1 resource, including the latest research and webinars.

Want access without creating an account?

You have 1 free members-only resource remaining this month.

1 free members-only resources remaining

1 free members-only resources remaining

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

You've reached your limit of free insights

Become a member to access all of Advisory Board's resources, events, and experts

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits include:

This content is available through your Curated Research partnership with Advisory Board. Click on ‘view this resource’ to read the full piece

Email ask@advisory.com to learn more

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.

Benefits Include:

This is for members only. Learn more.

Click on ‘Become a Member’ to learn about the benefits of a Full-Access partnership with Advisory Board

Never miss out on the latest innovative health care content tailored to you.